In 1976, President Gerald Ford formally recognized Black History Month; he implored Americans to “seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of Black Americans…throughout our history.” Last year, we chose to celebrate Black History Month by shining a light on the contributions of historic Black bakers whose impactful legacies have helped shape America’s baking traditions and culinary heritage. For over 400 years, Black Americans–among them bakers, chefs, and cooks of all stripes–have inspired our country’s foodways through their passion, skill, creativity, and entrepreneurship. We chose four historic Black bakers and featured each one in our weekly newsletter, focusing on the unique influence they each had in shaping our collective American culinary, social, and cultural history.

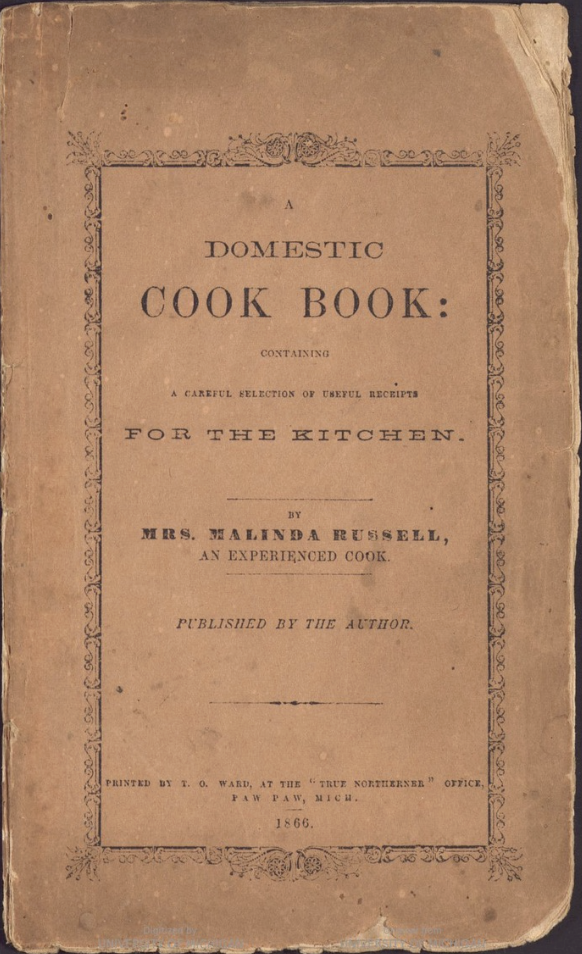

Malinda Russell (active 1830s – 1866)

I have made Cooking my employment for the last twenty years in the first families of Tennessee (my native place), Virginia, North Carolina, and Kentucky. I know my Receipts [recipes] to be good, as they always have given good satisfaction….I have put out this book with the intention of benefiting the public as well as myself.

So proclaimed Malinda Russell in the preface of A Domestic Cookbook: Containing a Careful Selection of Useful Receipts for the Kitchen; a cookbook she single-handedly wrote and self-published in 1866 while living in Paw Paw, Michigan. Little did she know when she penned the book’s 39 pages and 250 recipes (devoted in large part to baking), that it would eventually earn the distinction in 2000, when it was discovered, of being the first known cookbook published by a Black American and the first book to offer culinary advice by a Black American woman. Russell’s work offers a glimpse into fine cooking by a Black American woman from the pre-Civil War South who was never a slave and whose skills and point of view were geared toward serving up complex, cosmopolitan food inspired by European cuisine, not the Southern “soul food” style of cooking we mostly associate with Black American cuisine. According to the renowned Black journalist and culinary historian, Toni Tipton-Martin, Malinda Russell’s cookbook reflects “a sophisticated international kitchen” and “dispels the notion of a universal African-American food experience, which is why the term ‘soul food’ doesn’t work for so many of us.”

So who was Malinda Russell?

Born in Tennessee around 1812 (no birth records exist), Malinda Russell was a remarkably well-educated, free Black woman, descended from a grandmother who was an emancipated slave; a hard-working single mother; and a successful business owner esteemed by those in the communities where she served and set up shop. In Lynchburg Virginia, starting at age 19, she worked as a cook, lady’s companion, nurse, and laundress for prominent families. It was there that her culinary education began. She trained under a Black woman named Fanny Steward and was influenced by the 1824 publication of The Virginia House-Wife, by Mary Randolf, an upper-class white Southerner who, upon falling on hard times, ran a boarding house and wrote a food book. Randolf’s book is also notable for being the first published American cookbook on regional cuisine.

Four years after marrying her husband and bearing a child, Malinda was a young widow left to raise her disabled son alone. Ever resilient and resourceful, she returned to her native Tennessee, where on Chuckey Mountain she ran a boarding house, a laundry, and a very successful pastry shop for close to a decade. In 1864, near the end of the Civil War, misfortune struck again at the hands of a “guerilla” gang, who robbed her and forced her to flee the South. Headed north to Michigan (then billed as “the Garden of the West”), she eventually landed in Paw Paw, southwest of Kalamazoo, and proceeded to write her book, hoping that the proceeds would earn her a sufficient living and eventually passage to return home to her native Tennessee to recover what she had lost. Yet, within months of her book’s publication, the town of Paw Paw was destroyed by fire, including the library where her just-printed books were being housed. And that’s where Malinda’s story abruptly ends, destined to remain in obscurity until 2000, when low and behold, the sole surviving copy of the original A Domestic Cookbook found its way to the William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan, here in Ann Arbor, where it still resides today.

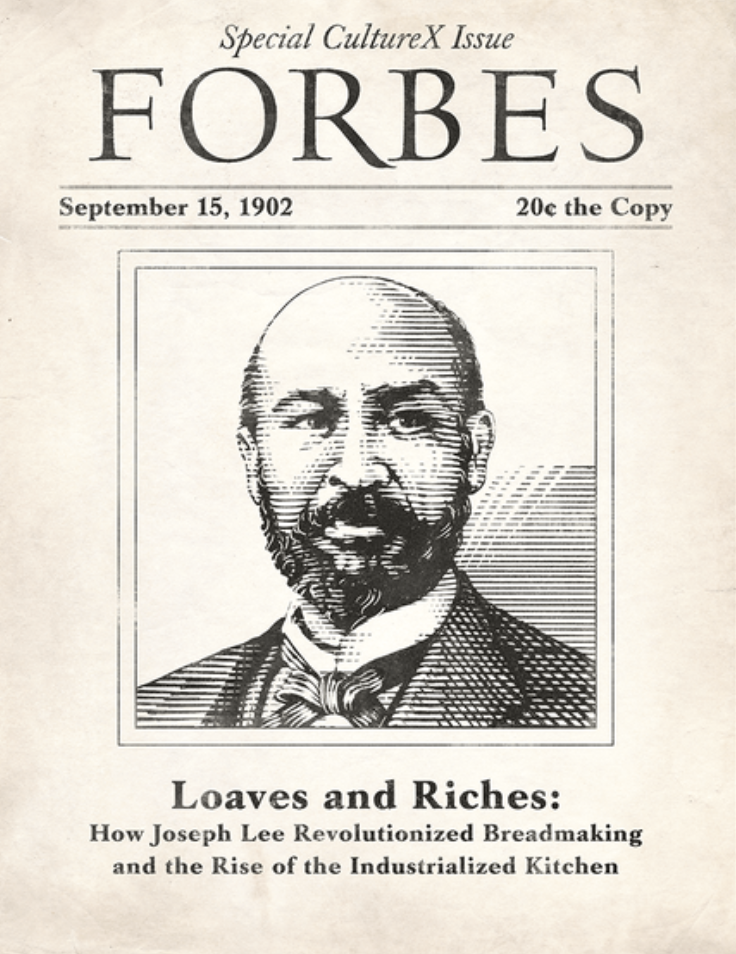

Joseph Lee (1849 – 1908)

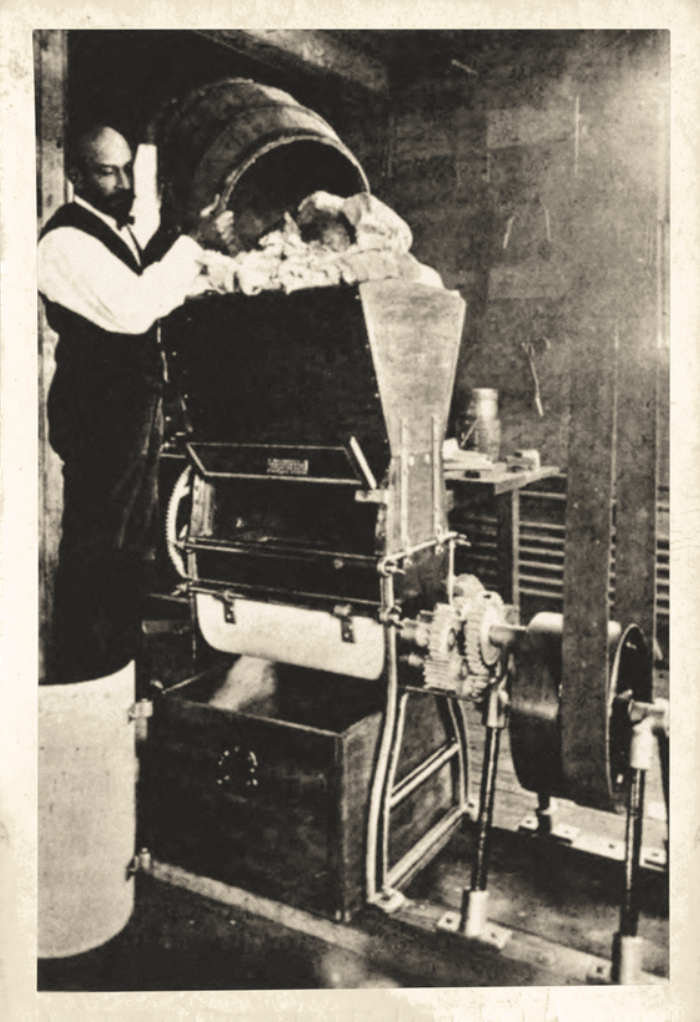

Boston-area entrepreneur Joseph Lee was a pioneer in the automation of bread and bread crumb making during the late 19th century. In the mid 1890s, he invented machines for use in the hospitality industry that automated the mixing and kneading of bread dough and that created crumbs from day-old loaves.

The son of enslaved parents, Lee spent much of his South Carolina childhood in bondage. He worked as a servant in Beaufort, then served for 11 years as steward in the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, where he devoted particular attention to bread making. By then a skilled chef and baker, Lee observed that the best bread was produced by evenly and thoroughly kneaded dough. By the early 1880s, the self-educated Lee had become a successful hotel and restaurant owner and caterer in Massachusetts.

Lee’s Lasting Impact

His Woodland Park Hotel in Auburndale was the birthplace of Lee’s most important and lasting inventions–machines that transformed baking and food preparation for much of the 20th century. His first, an automated bread-kneading machine he patented in 1894, yielded more bread than he and his staff could serve or sell. Troubled by the enormous amount of unsold bread his hotel restaurant and catering kitchens discarded because it was a day or more old and believing that breadcrumbs were better than cracker crumbs for coatings, Lee developed — and, in 1895, patented — a device to mechanize the tearing, crumbling, and grinding of bread into crumbs.

By 1900, Lee’s crumber was used by many of America’s leading hotels and was a fixture in hundreds of the country’s leading catering establishments. In 1902, he patented an improvement to his bread-kneading machine, hailed for superior kneading action that closely approximated the work of the human hand. For his important contributions as an inventor and entrepreneur, Joseph Lee was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2019.

Cleora Thomas Butler (1901 – 1985)

I might sum up my attitude about the art of cooking with this verse adapted from John Ruskin, learned somewhere, sometime ago:

To be a good cook means

Employing the economy of

Great-grandmother and the

Science of modern chemists.

It means much tasting

and no wasting.

It means English thoroughness,

French Art and Arabian hospitality.

It means, in fine,

that you are to see that

everyone has something nice to eat.

Ruskin

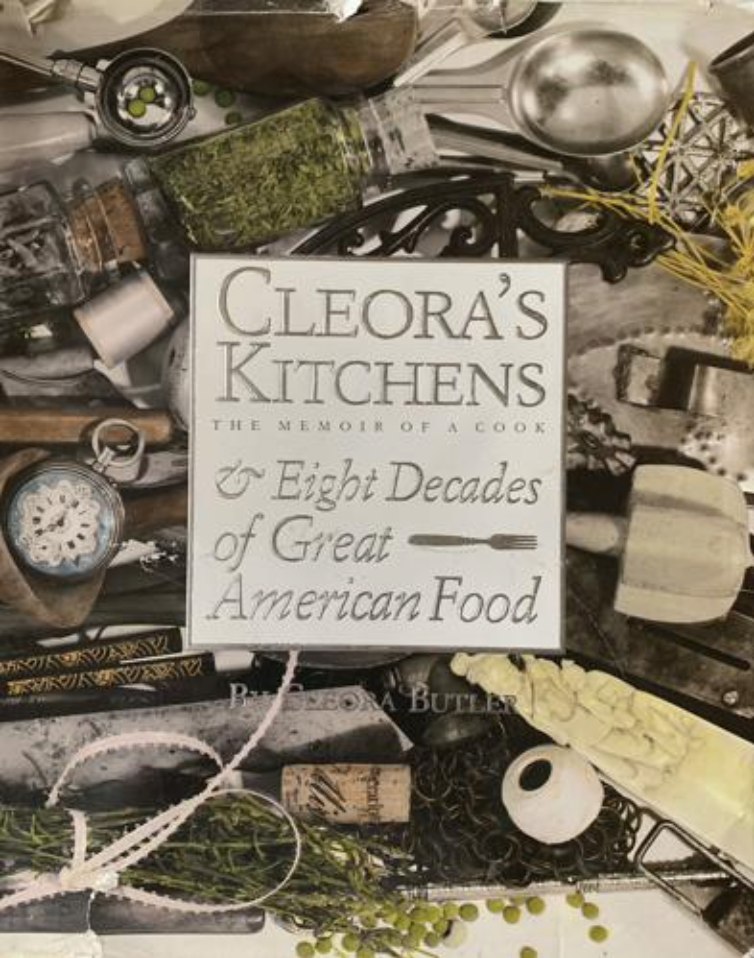

So proclaimed Cleora Thomas Butler in her groundbreaking cookbook and memoir, Cleora’s Kitchens: The Memoir of a Cook & Eight Decades of Great American Food, published in 1985 just months after her death at age 84. This combination cookbook/memoir by a beloved Black Oklahoma cook was ahead of its time and changed the direction of writing about cooking for a generation; in the years since it first appeared, books that weave together recipes with autobiography have become a distinct genre. As culinary historian Barbara Haber notes in her preface to the 20th-Anniversary edition (2005),

“…her book is a testament to how Cleora Butler was able to grow and develop as a cook throughout the eight decades of her cooking life in which she prepared not only traditional regional dishes of the Southwest but stylish meals of the 1970s and 1980s that were based on new ingredients. Her earliest recipes were for dishes she learned from her mother–hickory nut cake (with nuts that were gathered on the mountain behind her grandfather’s house), burnt sugar ice cream, grated sweet potato pudding, and corn fritters. Much later, however, she was cooking rice pilaf with pine nuts, tomato-mozzarella salad with red onions and anchovies, jalapeno cornbread, and a macadamia nut chess pie—ingredients and dishes that were new to most Americans.”

Front Cover of Cleora’s Kitchens: The Memoir of a Cook & Eight Decades of Great American Food (Tulsa, OK: Council Oak Books, 1985)

Through stories, menus, and over 400 recipes that unfold over eight decades, from the “early days” to the 1920s and through the 1980s, Cleora recounts her life story, celebrates other Black American women who cooked for a living, and charts the fascinating changes in American tastes, attitudes, availability of foods, and cooking and baking equipment and techniques. Her memoir also serves up a valid lesson on the Black American experience in the South and Southwest during most of the 20th century.

The History that Inspired the Book

Cleora Butler was born in Texas in 1901 and grew up in Muskogee, Oklahoma. The child of professional cooks, she learned her craft from her mother, Martha Thomas, as early as age 10. Later on, their home in North Tulsa, Oklahoma was a favorite destination for Cab Calloway and other Black musicians and entertainers, who often ate in private homes when traveling through the segregated South and Southwest. From those experiences in the kitchen with her mother, Cleora went on to become a cook for some of Tulsa’s most prominent oil barons in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s. At the same time, she continued to work with her mother to supplement her family’s income. In the 1940s, with the help of her mother, Cleora would bake some 150 pies a day in her own kitchen and by the early 1960s, she had opened up her own successful pastry shop and catering business. Following the death of her husband, George Butler, in 1967, Cleora closed the shop but continued her catering business on a limited scale, baked sweet rolls each week for the students at Holland Hall High School in Tulsa, and worked in the kitchen of Trinity Episcopal Church, preparing special dinners. She spent the last years of her life writing her groundbreaking cookbook and memoir.

Zephyr Wright (1914 – 1988)

“You deserve this more than anyone else.”

-US President, Lyndon B. Johnson, July 2, 1964

So declared President Johnson upon gifting Zephyr Wright, his personal cook, friend, and confidant for over 20 years, the pen he had just used, on July 2, to sign into law The Civil Rights Act of 1964. This impactful federal law prohibited discrimination in public places, provided for the integration of schools and other public facilities, and made employment discrimination illegal. It was the most sweeping civil rights legislation since the late 19th-century Reconstruction Era after the Civil War. At the heart of Johnson’s crusade to enact The Civil Rights Act were Zephyr Wright’s first-hand accounts of the discrimination she experienced when traveling by car through the segregated Jim Crow South–from Texas to Washington, DC and back—while working for the Johnson family. It was Zephyr’s stories–the hardship and humiliation of not being served in restaurants on the road and the difficulty of finding restrooms and hotels that would accommodate her—that in large part fueled Johnson’s commitment to correcting the abuses suffered by Black Americans.

Who was Zephyr Wright?

Born in 1914, Zephyr Wright grew up in Marshall, Texas and attended Wiley College, the first Black college in Texas to be accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Universities. Majoring in home economics, she was deemed the best student in her department by the college president, Matthew W. Dogan, who recommended her to work for the family of then US Congressman Lyndon B. Johnson from Texas. She was hired, on the spot, by Johnson’s wife, Claudia (“Lady Bird”) after their first interview in 1942. For the next three decades, as Lyndon Johnson rose up through the political ranks in Washington, DC—from Texas Congressman to Vice President under John F. Kennedy, and finally to President—Zephyr worked tirelessly to fulfill the family’s culinary needs and home comfort in both Texas and Washington DC. While Johnson was in Congress, his Washington DC home quickly became known for its food, as other politicians visited regularly and built relationships over Zephyr’s Southwestern chile con queso, spoon bread, and peach cobbler. Once Zephyr rose to Official White House Cook during Johnson’s presidency, few Washingtonians passed up the chance to dine with the First Family; and her recipes for pecan pie, pop-overs, and chili were frequent additions to the food pages of the nation’s newspapers–”Johnsons Dine a la Zephyr,” read the headline in the Long Beach (CA) Independent. The Pedernales River chili recipe was so popular it was printed on cards and passed out to White House visitors. Lady Bird Johnson once wrote, “I have yet to find a great chef whose desserts I like as well as Zephyr’s.”

Hungry for more?

- To learn more about Malinda Russell, her story, her recipes, and cookbook–including a free digital PDF download of the original housed at the William Clements Library at the University of Michigan–head to malindarussell.com.

- To learn more about Joseph Lee–his story and the machines he invented in the mid 1890s that transformed industrial breadmaking for the next century, head to the Forbes website and read Brianne Garrett’s in-depth article from 2021, “How This Unsung Black Entrepreneur Changed The Food Industry Forever—And Made A Lot Of Dough.”

- For free online access to a digital copy of Cleora Butler’s influential cookbook and memoir, head here to the Internet Archive.

- To learn more about Zephyr Wright, head to the HEMP&fork website and the The History Chicks podcast, “Episode 151: Zephyr Wright.” To hear from Zephyr Wright herself about her close 27-year relationship with Lyndon and Lady Bird Johnson as their personal cook and friend, head to the DiscoverLBJ website and read the transcript of her oral history interview recorded in 1974, which you can also download for free.

After a long, established career as a Ph.D. art history scholar and art museum curator, Lee, a Michigan native, came to the Bakehouse in 2017 eager to pursue her passion for artisanal baking and to apply her love of history, research, writing, and editing in a new exciting arena. Her first turn at the Bakehouse was as a day pastry baker. She then moved on to retail sales in the Bakeshop, followed by joining the Marketing Team and becoming the Bakehouse’s designated culinary historian. In addition to her retail sales and marketing work, she’s a member of the Bakehouse’s Grain Commission, co-author and editor of the Bakehouse's series of cookbooklets, and a regular contributor to the BAKE! Blog and Zingerman’s Newsletter, where she explores the culinary, cultural, and social history and evolution of the Bakehouse’s artisan baked goods.