Texting with Amy Emberling in July 2021:

Amy: Do you want to go to Uganda?

Me: Yes. Please.

Amy: …do you want to know what you’ll be doing?

In truth, I would’ve done just about anything. We were about a year and a half into Covid. Travel plans had been scrapped. I was lucky; I still had a job and had brought BAKE! into the realm of online classes. But I was itchy and looking for something outside the world of emails and vaccination rates and the ongoing uncertainty of the world.

Amy connected me to Ayelet Berman-Cohen. Through her Adama Foundation, Ayelet was partnered with Vibrant Community Initiatives, a group working with refugee women in the Oruchinga area in southwestern Uganda. Oruchinga comprises 13 refugee settlements, ranging in size from 13,000 refugees to over 100,000. Calling them refugee camps elicits images of tents and temporality; however, the reality is that people do not often return to their home countries and these settlements are more like cities, organized into neighborhoods by country of origin.

Amy connected me to Ayelet Berman-Cohen. Through her Adama Foundation, Ayelet was partnered with Vibrant Community Initiatives, a group working with refugee women in the Oruchinga area in southwestern Uganda. Oruchinga comprises 13 refugee settlements, ranging in size from 13,000 refugees to over 100,000. Calling them refugee camps elicits images of tents and temporality; however, the reality is that people do not often return to their home countries and these settlements are more like cities, organized into neighborhoods by country of origin.

Ayelet, along with the directors on the ground, Angella Kushemererwa and Sophie Karungi, had worked on sewing beautiful blankets to distribute to families. The current project was to build a bakery and teach baking skills in order for the bakers to learn a trade, earn an income, and distribute a portion of the day’s baked goods to children in the settlements.

So, would I be interested in going to teach bread baking and getting the bakery operational?

Absolutely.

Ayelet and I started talking. Her vision of teaching skills and feeding the most vulnerable was inspiring. She sent pictures and we started Zooming regularly. In August, she let me know that Jeffrey Hamelman, a world-renowned baker and long-time instructor at King Arthur Baking Company, was also very interested in going. We started assembling lists of needs, saw videos of the wood-fired oven, and figured out dates when we could both go. We talked about equipment needs. We got yellow fever vaccines and bumbled through visa applications. We coordinated flights and discussed expectations and hopes for our time there. We shared our hopes and expectations and, at the beginning of October, I flew to Boston, Jeffrey came down from his home in Vermont, and we boarded our flight to Doha, and then Entebbe in Uganda.

Uganda is a landlocked country in East Africa. It borders South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, Kenya, and Tanzania. Refugees come to Uganda from many different surrounding countries due to decades of civil wars, social, political, and religious regions. Uganda is a preferred destination due to the ability of refugees to integrate themselves into the community, whereas other neighboring countries have much more strict restrictions on movement and job options. Currently, Uganda hosts 1.5 million refugees, all supported by the United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR). Covid-19 has only exacerbated a pretty dire situation.

I thought we were going to the desert. Instead, we landed near Kampala, the capital, and drove seven hours through lush greenery and rolling hills. Acres of banana trees, cows and goats on the road, children carrying jerry cans down the road to fill with clean water. Bicycles laden with pineapples (25 cents each) toodled down the road. We passed over the equator and arrived, 40 hours later and very jet-lagged, at our hotel, chosen because it had hot water (most of the time) and a gregarious Ugandan proprietor who had spent years in Wisconsin and talked to us about ice fishing.

We had a day to handle our jetlag, visit the bakery, about 30 minutes outside Mbarara, near a base camp consisting of UNHCR offices and many international aid organizations, and make a plan for the first day with Angella and Sophie. Before we got to Uganda, our Zoom calls had often consisted of talking about potential breads we could make. We talked about sourdough. We talked about flatbreads. We talked about whole wheat flour and nutrition. Once we arrived, those ideas went out the window. The reality was that the bread that people were familiar with, what we ended up making and teaching, was a white bread, about 52% hydration and enriched with calcium (think Wonder Bread) that we made into both loaves and buns for the children. Bread ego, born of Instagram posts of crumb shots, had no place here. The basic need of something familiar, to fill a hunger in that moment, was our goal.

Day One

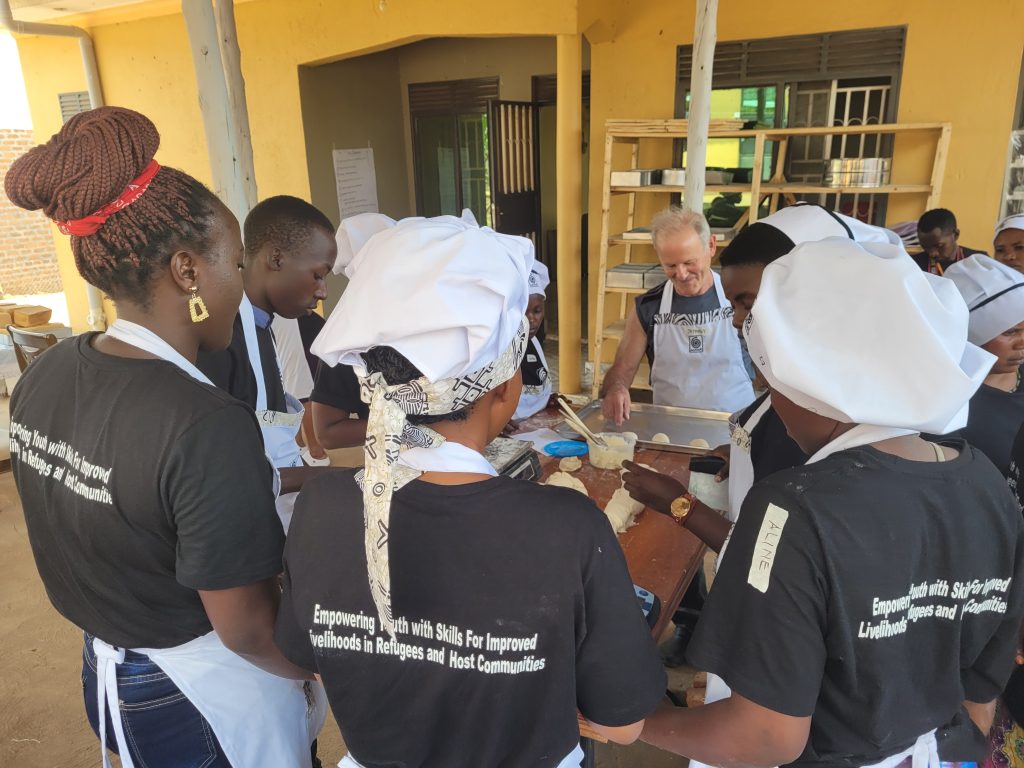

On Friday, October 8th, we showed up to 20 students, none of whom had ever baked bread before. They were primarily female, some with young babies strapped to their backs, who walked several miles to reach the bakery. There were a few young men. Everyone came from a refugee settlement. Some spoke English, some French, and everyone spoke some of the many dialects of their places of birth, including Runyoro, the mash-up of several common dialects found in that particular area of Uganda.

We mixed 40 kilos of dough, talked about the windowpane test, got familiar with the equipment and the layout of the bakery. Viani, a professional baker who built the oven, explained how to light the fires for the oven and the proofer. We talked about how to use the scales and demonstrated how to form the Pullman-shaped loaves. Sophie and Angella would translate. A group of local women catered a lunch of matoke (starchy bananas), rice, beans, and avocados. We ate and drank tea under our tarpaulin roof. When the first buns came out of the oven (slightly under proofed but still very edible) we cheered, raised them into the air, and took a million photos.

Day Two

We mixed 50 kilos of dough. I wrote the recipe on a large piece of paper and taped it to the wall; the students wrote the recipe in their notebooks. Jeffrey and I demonstrated different methods of shaping buns and showed them how, over time, they would be able to shape two at the same time. Viani showed us how to create steam in the proofer that was built behind the oven and we used this for our buns. We examined a loaf from the previous day and showed the holes that result from improper shaping. We talked about how we were learning and mistakes were okay. Claudine, a student who was quickly proving herself a leader, said, “A mistake is not a disease.”

Day Three

We mixed 90 kilos of dough which became 15 1-kilo loaves, 40 500-grams loaves, and 1000 buns. People stopped by—from different local aid groups, from the UN, from the road—wondering what we were doing, could they try some bread, could they become part of the group and get training?

Day Four

It rained and we huddled inside while the roof (tarpaulin and thatched wood) leaked. When the rain stopped, Sophie, Angella, Jeffrey and I took 40 bags of buns (6 in a bag) to the closest refugee settlement of 300 people. We looked at our van and thought we had enough buns. We thought we could hand out a bag of buns to each family. We drove into the center of the settlement. People began coming out of their houses. Young children, sometimes carrying an even younger sibling on their hip, gazed at us curiously. Some children saw our white faces and were terrified and ran away. As the number of people became larger, we abandoned our plan of handing out bags of buns and I started ripping the bags open, handing buns to Jeffrey, who handed one bun out to each child. There were more hands than there were buns. A woman told Sophie that, due to the rain and the inability to start a fire to cook any food, it was the only food they had eaten that day.

Days Five, Six & Seven

The tarpaulin was fixed and the next time it rained, we all stayed outside and stayed dry. The students were scaling and mixing without assistance from Jeffrey and me. They were shaping two buns at once. The loaves no longer had tunneling. We danced to Congolese music as Jeffrey made pizzas. I heard stories from 20-year-olds whose parents were killed, or missing, in conflicts, who did not know if their siblings were alive, who were subsisting on approximately $37 USD a month and asked questions about America (Did I know any celebrities? Was Donald Trump a good president?). Students would breastfeed their babies, chickens scratched around and ate our errant sim sim (sesame seeds), and the school-aged children whose parents were working in the bakery would run underfoot (Uganda’s schools are currently closed due to the pandemic and will not reopen until 70% of the population is vaccinated; currently, the number stands at 2%), helping us grease pans and asking when we were going to make cakes.

Day Eight

We drove to visit Nakivale, a settlement 48 square miles in size representing 12 different countries. UNHCR buses rumbled down the dirt road bringing new refugees. The gradients  of how long a refugee and their family had been in their home were expressed in whether a home was built of mud or brick, whether there was a curtain or a metal door. Children waved and yelled, “Mzungu!” (white person). The van twisted through neighborhoods filled with motorbikes, small shops, and churches. When we arrived, we found the de facto mayor of the Burundian section of the settlement who helped us hand out the buns and organize them properly. I pulled buns out of empty flour sacks, our technique much quicker and vastly more efficient than the first time. This time, we had enough buns. We brought our boombox and the children swivled around, relishing the music with a bun in their hands and crumbs on their mouths. As we drove out of the settlement, it was our turn to enjoy, as we found a group of breakdancers practicing and stopped to watch.

of how long a refugee and their family had been in their home were expressed in whether a home was built of mud or brick, whether there was a curtain or a metal door. Children waved and yelled, “Mzungu!” (white person). The van twisted through neighborhoods filled with motorbikes, small shops, and churches. When we arrived, we found the de facto mayor of the Burundian section of the settlement who helped us hand out the buns and organize them properly. I pulled buns out of empty flour sacks, our technique much quicker and vastly more efficient than the first time. This time, we had enough buns. We brought our boombox and the children swivled around, relishing the music with a bun in their hands and crumbs on their mouths. As we drove out of the settlement, it was our turn to enjoy, as we found a group of breakdancers practicing and stopped to watch.

Day Nine

UNHCR was doing a count of refugees down the road. The students sliced and packaged the bread from the previous day and took off down the road, returning two hours later, jubilant, because they had sold their first loaves. It was our last full day at the bakery. With Angella and Sophie, we talked about how to plan for the rest of the week, ways to organize the schedule, and how to maximize the capacity of the oven.

Day Ten

On the suggestion of a student, I made a certificate of completion. The students donned their chef coats and hats and I used my best Zingerman’s font to write their names out. We presented each student with their certificates and took one million pictures. We exchanged phone numbers, shed tears, and started the 40-hour trip back home.

Having been home for a little over a week now, I can sum up my experience in two observations: The first is that on Day One, all 20 students had never baked before, but by  Day Nine, they were selling their bread and receiving extremely positive feedback from their customers. They were sharing their bread with children and feeding people. That was incredible to see. The second is the disconnect between knowing that we can coexist on a planet where both Oruchinga and BAKE! exist is profound.

Day Nine, they were selling their bread and receiving extremely positive feedback from their customers. They were sharing their bread with children and feeding people. That was incredible to see. The second is the disconnect between knowing that we can coexist on a planet where both Oruchinga and BAKE! exist is profound.

Hungry for more?

- On November 9th, the Bread Baker’s Build of America is hosting an event, Raising Hope, to help raise funds for the bakery. This money will be used to help purchase equipment (a dough divider, a better generator for when the power goes out) and to pay the salaries (about $2.85/day) of the bakers. Over time, the bakery will become sustainable and other bakeries, in other refugee settlements in Ourchinga, will be able to train more bakeries and feed the need.

- Register for the free event (but consider donating if you can)

- Donate directly to the bakery initiative

- Get the recipe for Bakehouse White, the Bakehouse’s version of classic white bread

BAKE! Principal and Instructor

At the age of 4, Sara climbed on the kitchen counter to 'taste' vanilla extract. Disappointed by the taste (how could something that smelled so good taste so bad?), she was caught by her mother and had to sheepishly explain what she was up to. Fast forward ten years and Sara was selling homemade sandwiches and cookies to her friends at lunch and still running lemonade stands with her best friend. This love of all things food, and especially baking, led Sara to the Culinary Institute of America where she got her degree in baking and pastry arts. She baked and cooked her way across the country, working everywhere from NYC to San Francisco, Atlanta, Alaska, North Dakota, and even Cambridge, England.

Sara received her master's degree in hospitality management from Cornell University, where she helped teach and develop curriculum for an undergraduate restaurant course. After years of wondering how Zingerman's made their deliciously perfect Cosmic Cakes, she is thrilled to be a part of the team and learn the secrets to pass on to BAKE! students.

I’ve taken in-person and virtual BAKE! classes with Sara and both were wonderful learning experiences. Thank you for sharing your adventure in Uganda with us!

Sara – I so enjoyed reading about your adventure and love of teaching. You are a blessing to us Zingerman’s students and now to those around the world. God Bless

Sara, thank you for sharing such a profound experience! You and your team changed the lives of those young bakers – most certainly a fait accompli!