Here at the Bakehouse, we’re now in the home stretch of the holiday season, when traditional pie-making in the pastry kitchen kicks into high gear and our pies fly out the door to grace many a holiday table. For this year’s holiday pie extravaganza, we celebrate Bakehouse Managing Partner Amy Emberling’s all-time favorite—our classic pecan pie. “This is my favorite Bakehouse pie,” Amy proclaims in the headnote to the make-at-home recipe in our cookbook, Zingerman’s Bakehouse, “just because I enjoy it and also because it fits our mission perfectly—full-flavored and traditional.” The pie also happens to be as American as it gets—move over apple pie!—created as it was in the South, home to the only tree nut indigenous to the United States—the all-American pecan.

America’s Native Nut – Some Culinary History

The quiet little pecan, delicately sweet and so rich tasting, is as American as, well, pecan pie! There’s no doubt about it—the pecan tree, which is a kinsman of the hickory and walnut family, was growing wild in the United States long before any newcomers arrived here.

—From “Pecans—The True Blooded Americans,” by Zel and Reuban Allen, 2004.

Pecans, with their rich buttery taste and crisp, crunchy texture, not to mention their heart-healthy nutritional benefits, have become firmly embedded in our American heritage and culinary traditions. The nut’s storied past as a nutrient-rich food source and ultimately a dietary staple begins with Native American tribes, who for centuries lived among, or traveled through, the forested lowlands along the Mississippi River and its tributaries where the pecan tree grew wild. This vast native pecan-growing region extended from Illinois down to the Gulf Coast, and into Eastern Texas and Mexico.

A member of the hickory family and closely related to the walnut, pecans have the unique distinction of being the only major tree nut indigenous to North America and have not been found to grow naturally anywhere else in the world. The stately trees that produce them (Carya illinoinensis), which can grow to over 100 feet tall and live to be over a thousand years old, first took root in the wild along those rich fertile river banks throughout the South Central region of the United States more than 100 million years ago.

A Native American Culinary Staple

Native Americans had been eating pecans, foraged from native wild trees in the fall months, for several millennia before the arrival of Europeans in the 16th century. The name “pecan” stems from paccan, a Native American word coined by the Algonquins, which, roughly translated into English, means “nuts requiring a stone to crack.” And crack them they did, utilizing the nutmeat in all sorts of culinary preparations. They pressed them to get oils for seasoning, ground them into meal to thicken stews, cooked them with beans, corn, and squashes, and roasted them for long hunting trips to sustain them when food along the journey became scarce. Another such preparation, notes historian Frederic Rosengarten, Jr., author of The Book of Edible Nuts (1984), was powcohicoria or “hickory milk,” in which “paccan kernels were pounded into small pieces, cast into boiling water, strained and stirred.” This rich nutty concoction would then be added to broth to thicken it and to corn cakes and hominy as a seasoning. When fermented, powcohicoria also became an intoxicating drink.

The American Pecan Trade Takes Root

By the 18th century, pecans were not just a prominent staple of the Native American diet; the tasty nut had also become a valuable currency of exchange as Native American tribes began trading with European explorers, fur traders, and colonists. “As Native Americans journeyed and camped along their trading routes,” notes one food historian, “they planted pecan trees [from wild seedlings] to assure that they and their progeny would have a steady supply of the precious nuts for trading. When the trees began to bear fruit [in the fall], the [Native Americans] would plan their routes to take advantage of the harvest.” Their precious pecans paid for goods such as hides and mats from frontier fur traders, who were the first to carry the nuts to the Eastern Seaboard. Once there, pecans generated a great amount of horticultural and culinary interest among the European and British colonists and America’s Founding Fathers, so notes the horticulturist and pecan specialist, Lenny Wells. George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, for starters, were especially fond of the nut and were early promoters. Beginning in the late 1770s, both men, after acquiring wild seedlings and nuts from the Mississippi River Valley, planted and grew pecan trees on their respective Virginia plantations–Washington at Mount Vernon and Jefferson at Monticello. Washington was even known to carry pecans in his coat pockets as a snack.

The Growth of an Industry

This wide-ranging embrace of the pecan among the American colonists and Founding Fathers soon fostered efforts to domesticate pecan tree cultivation for purposes of trade, with the ultimate aim of turning the nut harvest into a cash crop. But growing pecan trees was not easy, as the early pioneers of horticultural domestication discovered, through trial and error, throughout the first half of the nineteenth century. Their early attempts at pecan tree cultivation in Texas and Louisiana, whether from seedlings or nuts from a favored wild tree, yielded unpredictable results, since seedlings never produce an exact copy of the parent tree. This inconsistency in tree cultivation limited the trade in pecans until the mid-nineteenth century when “the development of successful [pecan] cultivars through budding or grafting changed all that,” notes Edgar Rose in his summary entry on pecans in The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink (2007).

The first pecan tree grafts to bear fruit were achieved in Louisiana in the mid-1840s by an enslaved gardener named Antoine, who tended the gardens at J. J. Roman’s Oak Alley Plantation on the Mississippi River, west of New Orleans. Antoine’s consummate skills at grafting led to the successful cultivation of some 126 trees on the sugar cane plantation. What is more, Antoine’s cultivars produced a variety of pecan with a shell so thin it could be cracked with one’s bare hands, making the nutmeat inside easy to extract. The variety was dubbed the “paper shell” pecan and later on was named the Centennial Variety when it was entered in a competition at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, where it won a prize.

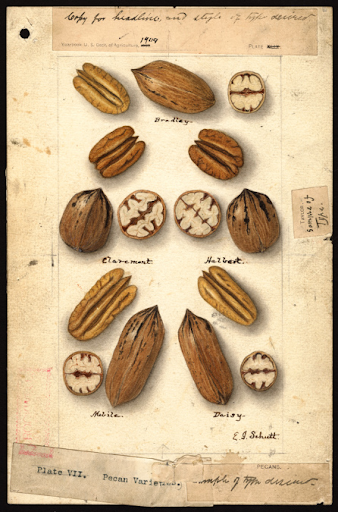

Louisiana plantations in the Mississippi Delta continued to be hot spots of domesticated pecan tree cultivation with the next horticultural breakthrough coming at the hands of Emil Bourgeois, starting in 1877 on the Rapidan Plantation in St. James Parish. His efforts resulted in wide acceptance of pecan tree cultivars achieved through selective grafting and laid the foundation of modern pecan tree orchards. “At the end of the nineteenth century,” Edgar Rose notes, “tree nurseries used Bourgeois’s techniques to develop cultivars that combined good taste, large kernel size, high yield, and resistance to insects, diseases, and adverse climatic conditions.” These techniques also “enabled the simultaneous maturing of all the nuts on the tree,” which was of great importance for economical harvesting. It was these breakthroughs in tree cultivation that triggered the startup of vast commercial pecan orchards in Georgia and Texas, comprised of both grafted cultivars and native trees.

Today, pecans are grown commercially in native groves and cultivated tree orchards in 15 states throughout the South, Midwest, and Southwest. They’ve evolved into a highly coveted and internationally traded crop, so much so that American growers, concentrated mostly in Georgia and Texas, produce over 80% of the world’s pecan supply, with their trees yielding more than 300 million pounds of the thumb-sized, plump, brown nuts every year. All the varieties grown commercially today—Cape Fear, Desirable, Moreland, Stuart, Western Schely, and Pawnee, to name just a few—are derived, through selective grafting, from the native pecan tree groves that grew wild in North America for millions of years.

And Then There was Pie—At Long Last!

As a good daughter of the South practically weaned on pecan pie, I had always assumed that it dated back to Colonial days. Apparently not. Still, I find it difficult to believe that some good plantation cook didn’t stir pecans into her syrup pie or brown sugar pie. Alas, there are no records to prove it.

—Jean Anderson in American Century Cookbook: The Most Popular Recipes of the 20th Century, 1997

Pecan pie is a great dessert at any Southern table, all fall — including Hanukkah and Christmas.

—Alex Willson, a 4th-generation pecan farmer from Sunnyland Farms in Albany, Georgia, 2016

A true Southern favorite on the holiday dessert table, pecan pie, as we know and love it today, is a relative newcomer to the American pie-making tradition, which is quite surprising given the pecan’s long-standing native culinary heritage. The first recorded recipes for the sweet, nutty, pie, date only to the 1880s and 1890s, appearing in various publications touting Southern food, while published American recipes for its holiday pie compatriots—apple pie and pumpkin pie—by contrast, are centuries old. Yet, I suspect, as does Jean Anderson, author of the American Century Cookbook: The Most Popular Recipes of the 20th Century (1997), quoted above, that bakers and cooks on Southern plantations in Louisiana, Texas, and Georgia, where the pecan growing industry first took root, were indeed stirring pecans into their syrup, molasses or brown sugar pies long before the late 19th century; perhaps they just didn’t bother to write anything down. Noted Southern food historian, John Egerton, posits a similar notion in his book Southern Food: At Home, on the Road, in History (1987): “We heard the claim that Louisianans were eating pecan candies [i.e. pralines] before 1800, and with the sugar and syrup produced from cane at that time [grown on Louisiana plantations], it is conceivable that they were eating pecan pies, too, but there are no recipes or other bits of evidence to prove it.”

Such speculation aside, food historians cite pecan-rich Texas as the epicenter of the earliest printed recipes for pecan pie, which began popping up in Texas cookbooks and newspapers in the 1880s. Soon, recipes for pecan pie from the Lone Star State were appearing in magazines with national circulation, such as this snippet of one published in the New York magazine, Harper’s Bazaar, in 1886:

Pecan Pie

Is not only delicious, but is capable of being made a ‘real state pie,’ as an enthusiastic admirer said. The pecans must be very carefully hulled, and the meat thoroughly freed from any bark or husk. When ready, throw the nuts into boiling milk, and let them boil while you are preparing a rich custard. Have your pie plates lined with a good pastry, and when the custard is ready, strain the milk from the nuts and add them to the custard. A meringue may be added, if liked, but very careful baking is necessary.”

—“Pecan Pie,” Harper’s Bazaar, February 6, 1886 (p. 95)

By the late 1890s, “Texas pecan pie” had a national following, with a more fully formed recipe appearing first in the Ladies Home Journal and reprinted in newspapers as far north as Indiana:

Texas Pecan Pie

One cup of sugar, one cup of sweet milk, half a cup of pecan kernels chopped fine, three eggs and a tablespoonful of flour. When cooked, spread the well-beaten whites of two eggs on top, brown, sprinkle a few of the chopped kernels over. These quantities will make one pie.

—Ladies’ Home Journal. Reprinted in—Goshen Daily Democrat, [IN] November 26, 1898 (p. 6)

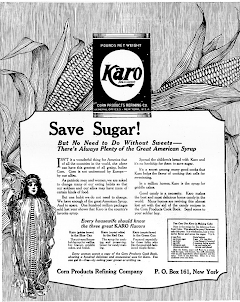

These early Texas versions of pecan pie, which called for boiling the nuts in milk while preparing a rich, sweet pecan-laced custard and then topping the pie with a browned, eggwhite meringue, are rather different from today’s, and are thought to have been a variation of a German nusstorte (traditionally a walnut tart), brought to Texas by German settlers. It wouldn’t be until the early 20th century that pecan pie would become the American classic we know now. For that, we have the American manufacturer of the Karo brand of corn syrup, to thank. Launched by the Corn Products Refining Company of New York and Chicago in 1901, the corn syrup was first touted in national magazine print advertisements as a flavorful, “food-energy” sugar substitute during World War I and throughout the 1920s and 1930s, in the midst of recurring sugar shortages. By the 1940s, the company had perfected a recipe for pecan pie with which to pitch it’s light and dark corn syrup, whether on the syrup container itself or in a plethora of print advertisements appearing in national magazines. Moreover, it did not take long for the popular pie recipe to make its way into such national cookbook icons as The Fannie Farmer Cookbook and Joy of Cooking.

It was this massive advertising campaign, coupled with the nation-wide distribution of Karo syrup, that introduced people, not just in the South but all over the country, to pecan pie, showing them just how easy the sweet, nutty convection was to make. The Karo recipe, often touted as Karo “Prize” Pie, A Treat for the eye—a thrill to the taste—and so easy to make! and In the Tradition of the Old South, was and still is rather simple: a sweet, caramelly mixture of the corn syrup along with eggs, sugar, butter, vanilla extract, and pecans, all of which is then poured into a traditional single pie crust and baked to a deep dark brown with a crunchy layer of pecans rising to the top.

The Bakehouse’s Take on the American Classic

Utilizing the Karo recipe as a foundation, the Bakehouse has long since perfected its own iteration of pecan pie. In our cookbook Zingerman’s Bakehouse, Managing Partner Amy Emberling shares what makes our take on the American classic so flavorful and special:

…the difference between a good version and a great version is the quality of ingredients and their proportions. The pie filling, clearly the star of the show, is…special because of the muscovado brown sugar, which has exponentially more flavor than standard brown sugar. Real vanilla extract and flavorful butter are also critical. Finally, not all pecans are the same. The variety and how they are grown, harvested, and stored makes a difference in the intensity of their flavor and the crispness of their texture. We use what are called mammoth halves (big ones! avoid chopped pieces) and include them generously. The varieties we use are Western Schley and Pawnee, both of which are known for their good flavor.

Although the filling is the star of this pie, the crust is an important partner in the deliciousness. Its crispness is a nice contrast to the smooth filling, and the toasty butter flavor is a good complement. Every star needs a strong supporting actor, right?

Watch Amy Make the Bakehouse’s Pecan Pie

Last year in November, SEEN Magazine, a monthly local life-style guide for Metro Detroit, featured Amy in their “SEEN in the Kitchen” video series, making our Pecan Pie from start to finish. Watch below to see Amy in pie-making action over at BAKE!, our hands-on baking school. And head here for the nice profile article on her and the Bakehouse, as well as the Pecan Pie and Pie Dough recipes from the Zingerman’s Bakehouse cookbook. And don’t forget to stop by the Bakehouse shop to pick up or order online our oh-so-tasty classic pecan pie for your holiday table!

I have been trying different Pecan Pie recipes for over a year now (had to learn after moving to the south!). This one, by far, turned out the best! I did what other’s said & didn’t beat the egg’s too much. I didn’t have dark corn syrup so I used light. I think next time I will use brown sugar instead. The only alteration I did was I just dumped the pecans in the pie shell and then poured the egg/sugar mixture over them and cooked. I also mixed the water with cornstarch first…maybe that made the difference! VERY GOOD!… Read more »