Rhubarb Pie / Rhubarb Pie

It might rain tomorrow / Better get some before I die

Save your lemons / Get ’em up in the tree

Save your peaches / They really don’t get to me

Talk about somethin’ sure gonna / Make me shout

Go on get some rhubarb pie / That’s what it’s all about

— lyrics from “Rhubarb Pie,” by John Fogerty, 2004

My Love for Rhubarb Pie: A Favorite Rite of Late Spring and Early Summer!

Yes, I admit it; I’m an unapologetic purist when it comes to rhubarb pie. The addition of strawberries or any other fruit embellishment is sacrilege to me, serving only to diminish rhubarb’s glorious citrusy tartness! You see, I grew up savoring with great relish the pure, unadulterated rhubarb pie my father would bake every spring and early summer, as soon as the Michigan rhubarb growing in the backyard came into season. He’d begin with a simple filling of freshly picked rhubarb; some sugar (not too much, though, we loved that rhubarb tang!); a dash of flour or cornstarch, depending what was on hand; a pinch of salt; and pats of butter, which he would then tuck into a flaky double pie crust. Never mind, that my father, a brilliant orthodontist who also happened to be an amazing off-the-cuff, improv cook and occasional baker, often forgot, in his characteristic absent-mindedness, the just-baked rhubarb pie he had placed beneath the broiler to render the deep golden brown top crust he so desired; the end result being what my siblings and I lovingly referred to as “Bob’s flaming rhubarb pie.” And we savored every bite of those pure, unadulterated, slightly sweet and tangy tart pies, scorched top crusts and all! We couldn’t get enough!

Enter Zingerman’s Bakehouse and Simply Rhubarb Pie

So, imagine my utter delight and excitement, when I first came to work in the Bakehouse pastry kitchen, some four years ago, right smack in the middle of Michigan rhubarb season, to find that we were rustling up the same pure, unadulterated, simple, double-crusted rhubarb pie I so loved growing up, only now to golden brown perfection, minus my father’s broiler mishaps. And what a pure and flavorful marvel the Bakehouse’s Simply Rhubarb Pie truly is! It’s my favorite, hands down! And every year, come late spring/early summer, I wait in utmost anticipation for that crop of Michigan rhubarb to arrive at the Bakehouse, always ringing in the season’s bounty with John Fogerty’s joyous song, “Rhubarb Pie.”

(Head here to see Fogerty and his band performing “Rhubarb Pie” live at the Austin City Limits Music Festival in 2004.)

Now for Some Good Old Rhubarb History

Native to Asia, rhubarb was first discovered along the banks of the River Volga in Siberia, and by 2700 BCE, it was being cultivated in China for medicinal purposes. As early references to rhubarb in botanical and historical texts affirm, the plant’s dried root was especially effective in treating gastrointestinal ailments and complaints. As one historian notes, “it soothed the bellies of emperors and paupers for centuries before it rose to any kind of culinary occasion.”

“Silks, satins, musk, rubies, diamonds, pearls, and rhubarb.”

– Ambassador to Samarkand, Uzbekistan, 1405

From China, medicinal rhubarb later made its way back to Russia, via the Silk Road, and from there went west into Europe. Used widely in European pharmacy from the 15th thru the 17th centuries, rhubarb eventually migrated from the apothecary to the kitchen, becoming a popular food plant in the 18th century, all thanks to the British and French. They were the first to discover that the plant’s petiole, or stalks, were edible and could be employed in the making of tasty sauces for savory meats or fillings for tarts and pies. Since rhubarb, on its own, is incredibly tart, requiring some kind of sweetener to tame it, it’s no coincidence that its culinary use happened to evolve just as the availability of sugar, once a luxury only for the wealthy few, became more widespread and affordable.

Culinary rhubarb crossed the Atlantic to North America in the first half of the 18th century, when John Bartram (1699-1777), the well-known Anglo-American colonial botanist, horticulturist, and explorer, cultivated two different species of the plant in his farm garden, outside Philadelphia, from seeds sent to him from England in 1739 by his associate and fellow plant enthusiast, Peter Collinson, a British merchant based in London. In his letter to Bartram, which accompanied the seeds, Collinson sang rhubarb’s culinary praises, writing that the plant makes “excellent tarts before most other Fruits fitt [sic] for that purpose are ripe…” He then shared a simple recipe for a rhubarb tart, which is the earliest known reference to rhubarb pie, in America (simply rhubarb all on its own—no strawberries or other fruit embellishments in the mix):

All you have to do is to take the stalks from the root, and from the leaves; peel off the rind and cut them in two or three pieces, and put them in crust with sugar and a little cinnamon; then bake the pie, or tart: eats best cold. It is much admired here [in England], and has none of the effects the roots have. It eats most like gooseberry pie.

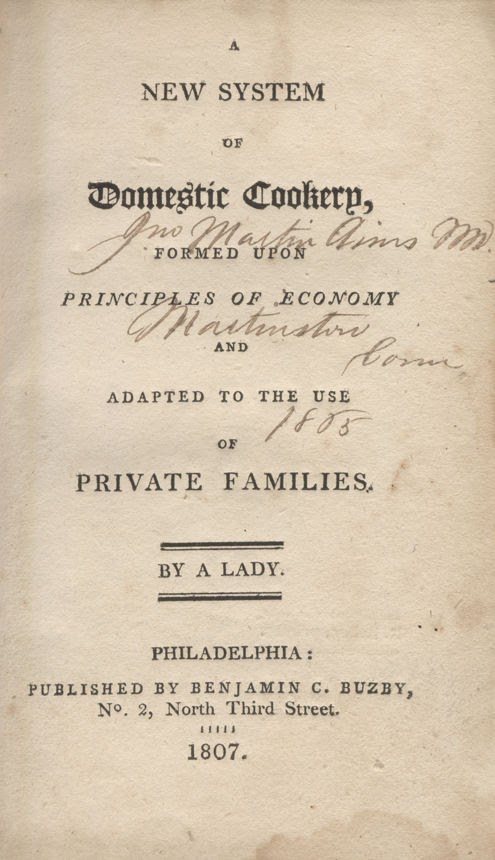

It did not take long for rhubarb’s popularity as a culinary staple for jams, sauces, preserves, and especially pies, to take firm root in America. The first published recipe for rhubarb pie, pure and simple, appeared in the 1807 American edition (published in Boston and Philadelphia) of the most popular English cookbook of the first half of the 19th century: Maria Rundell’s A New System of Domestic Cookery: Formed Upon Principles of Economy; and Adapted to the Use of Private Families, first published in London in 1806. Her recipe for a “Rhubarb Tart,” again pure and simple, doesn’t deviate much from the recipe Collinson had dashed off in his letter to Bartram decades before:

Cut the stalks in length of four or five inches, and take off the thin skin. If you have a hot hearth, lay them in a dish, and put over a thin syrup of sugar and water; cover with another dish, and let it simmer very slowly an hour; or do them in a blocktin saucepan. When cold, make into a tart, as codlin. Line the bottom of a shallow dish with paste, lay the [rhubarb] in it, put sugar over, and lay little twists of paste over in bars. (pp. 160-161).

Rubarb’s popularity quickly spread throughout New England, when an unnamed Maine gardener introduced the plant to Massachusetts growers with seed that he, like Bartram, had obtained from Europe. From New England, rhubarb migrated to the Midwest territories with the settlers. By 1830, rhubarb appeared in American seed catalogs; it was being sold in produce markets; and its use as a culinary staple, especially in pies, was rampant, earning it the nickname “pie plant.”

Well suited to its cultivation, both in terms of soil and climate, Michigan has been one of the largest producers of field-grown rhubarb in the United States for decades. In fact, in the 1950s, Macomb County, in Southeast Michigan, then an agricultural hub, was considered the “Rhubarb Capital of the World.”

A Burning Question: Is Rhubarb a Fruit or a Vegetable?

Botanically speaking, rhubarb is a perennial vegetable, rich in fiber and antioxidants, that grows best in cooler, temperate climates with little or no maintenance and ripens in late spring. Known for its reddish stalks and tart taste, it may surprise some to know that rhubarb belongs to the buckwheat family, Polygonaceae. Here in America, most folks consider rhubarb’s petiole, or stalk, a fruit. In fact, in 1947, the U.S. Customs Court in Buffalo, NY made the designation official, ruling that rhubarb should be considered a fruit since it is used typically as a fruit would be. Whichever way you lean, there’s no denying rhubarb’s incredible culinary versatility and that it makes one fantastic pie!

Back to the Bakehouse’s Simply Rhubarb Pie

Not to overstate the obvious, but the Bakehouse’s Simply Rhubarb Pie is just that; a lovingly crafted traditional pie, pure and simple, with culinary roots to the first such pies made here in America. We start with that simple filling of fresh, seasonal Michigan rhubarb and a bit of sugar, using as little as possible so the tart-sweet flavor of the rhubarb really sings! And then we tuck that pure and simple filling into our all-butter double pie crust made with freshly milled, organic high-extraction wheat flour we get from Janie’s Mill in Ashkum, Illinois. And into the oven the pie goes until the rhubarb juices are bubbling through heart-shaped vents and the crust is a deep golden brown.

Get it while you can, since the pie goes on vacation when the local rhubarb crop runs out, likely in mid-July.

John Fogerty croons it best in the closing verse of “Rhubarb Pie”:

Come on in my kitchen / Lord I wish you would

Roll my eyes and shut my mouth / This rhubarb sure is good!

Hungry for More?

- Watch our pastry team put together this marvelous pie in the video short, “The Simple Life of Simply Rhubarb Pie.”

- And if you’re looking for even more rhubarb deliciousness, try our amazing rhubarb cheesecake and rhubarb yogurt cup made with organic, grass-fed Hiday Family Farm yogurt.

- Make our Simply Rhubarb pie at home, the recipe can be found in our cookbook, Zingerman’s Bakehouse. Pick up a copy in our shop or have one shipped to your door.

- Join us on July 1st for our virtual Berry Delicious Fruit Pies class and learn how to make both our Simply Rhubarb and Jumbleberry pies.

After a long, established career as a Ph.D. art history scholar and art museum curator, Lee, a Michigan native, came to the Bakehouse in 2017 eager to pursue her passion for artisanal baking and to apply her love of history, research, writing, and editing in a new exciting arena. Her first turn at the Bakehouse was as a day pastry baker. She then moved on to retail sales in the Bakeshop, followed by joining the Marketing Team and becoming the Bakehouse’s designated culinary historian. In addition to her retail sales and marketing work, she’s a member of the Bakehouse’s Grain Commission, co-author and editor of the Bakehouse's series of cookbooklets, and a regular contributor to the BAKE! Blog and Zingerman’s Newsletter, where she explores the culinary, cultural, and social history and evolution of the Bakehouse’s artisan baked goods.

Down under the oak, in a partially shaded area by the old John Deere – that’s where Grandma and Grandpa’s rhubarb patch grew. Glorious tart stalks that always made me feel a bit like a renegade when snapping off a long pink stem and taking a bite. Still does.

Enjoyed your story about the extra-crispy topping!

Hi Teri – Happy to know that there are other folks out there who’ve loved rhubarb since childhood! I too, have been known to snack on stalks freshly picked – I sure love that tangy tartness!

I love rhubarb also. I grew up in suburban Detroit and my mom had a rhubarb patch. We used to cut the leaves off the stalks to make hats. My mom always made plain, unadulterated and delicious rhubarb pie. No strawberries allowed!

I now have three bunches of rhubarb in my garden and make two or three every year, using my mom’s recipe. We usually freeze enough for a rhubarb pie at Easter.

Btw, Macomb County is in southeast Michigan.

Hi Carolyn – thanks so much for your comments. I can’t say we were as creative with our backyard rhubarb as you were. Would love to have seen those hats you made! Thanks also for catching my geographic faux pas. I do indeed know that Macomb County is in Southeast Michigan. In fact, I have a dear friend I grew up with who lives in Mt. Clemens and also enjoyed Bob’s flaming rhubarb pie! I appreciate your editorial eye and have made the correction!